6 stars

First Sentence: When the siege and the assault had ceased at Troy,

and the fortress fell in flame to firebrands and ashes,

the traitor who the contrivance of treason there fashioned

was tried for his treachery, the most true upon earth—

it was Aeneas the noble and his renowned kindred

who then laid under them lands, and lords became

of well-nigh all the wealth in the Western Isles.

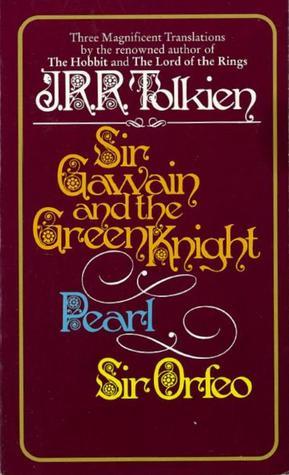

Thoughts: Tolkien gave the world two gifts. The first was as the father of modern fantasy, and the second was in translating and sharing the medieval literature that inspired him to create his own world. Of course, these poems were published after his death by his son Christopher,* but he intended to publish them when he finished fiddling with them.

Sir Orfeo is a medieval English retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Euryidice. In this version, Queen Heurodis is kidnapped by the King of Faerie right under Orfeo’s nose. He goes on a quest to find her, and this time remembers not to turn around before they return to the real world. I love a happy ending.

Pearl is an allegorical poem. The narrator is distraught after the death of his two-year-old daughter Margery (Pearl). He’s crying over her grave when he sees a heavenly light. His daughter appears before him decked in pearls. They have a dialogue over purity and Heaven and all that good stuff. The narrator doesn’t want Pearl to leave him again, so she lets him follow her to the outskirts of Heaven. He gets a glimpse of the life to come, but when he tries to go in he’s thrown back to Earth.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is the most famous of the poems. It’s been fully accepted into the Canon and is taught in school, which makes me wonder if the version I read in high school was Tolkien’s. Sneaky way to get into the curriculum, Professor. I’ve always loved this story and its version of Gawain which is much better than the Gawain in Malory-based Arthurian legend.

We all know the story of how the Green Knight showed up at Arthur’s Christmas feast and asked someone to chop his head off and Gawain did it and the knight picked up his head and told Gawain to meet him next Christmas and he would exchange a blow for a blow. Then Gawain goes on his journey and ends up at a castle with a very hospitable host and hostess. The host goes hunting for three days while the hostess flirts with Gawain, and at the end of the day Gawain and the host exchange what they gained. Except Gawain doesn’t give him the green girdle the hostess gives him so when he meets the Green Knight he gets a cut on his neck for being dishonest.

That’s all well and good, but the thing about literature, real Literature, is that it’s a living being that can be interpreted and re-interpreted. Which is a roundabout way of saying that this poem inspired what is probably my favorite movie of this century, The Green Knight. It is everything I ever wanted in a movie. If you haven’t seen it, you absolutely must.

*I appreciate Christopher Tolkien’s work sharing his father’s unpublished works but I think he was taking it too far near the end. I half-expected him to publish The Annotated To-Do Lists of J.R.R. Tolkien before he died.